Agritech services can help farmers meet global food demand

AS a young boy in northern India, Himanshu Gupta’s grandmother would often dilute the milk with water to ensure there was enough to feed their lower-middle-class family of sixteen. Rising prices for milk meant the family couldn’t afford to buy more.

"Back then, we didn't have time to understand the nuances of why or what was happening," he says. "But many of these problems, like food inflation… climate change is one of the significant factors playing into it."

Fast-forward a few decades, and Gupta co-founded ClimateAi from his dormitory room at Stanford University, United States, one of the world’s most prestigious universities. He now wants to help more than 500,000 million farmers globally in just six years.

Leveraging today’s rapid advancements in 'agritech' – the use of digital tools and technology in farming – is crucial to helping farmers adapt to the climate crisis and strengthen global food security. It also makes good business sense, as Gupta says climate adaptation across all sectors is a $1 trillion opportunity.

“This year, we see an inflexion point in adaptation, going from a philanthropic agenda to a corporate agenda,” Gupta told the World Economic Forum.

ClimateAi works with more than 50 corporations in food, agriculture, and beverage supply chains. Companies are now more engaged because they “appreciate that today’s level of volatility in the value chains because of climate change is unprecedented.”

How can AI help?

One-third of the Earth's soils are already degraded, with the equivalent of one football pitch of soil being eroded every five seconds, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) points out.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has the potential to help relieve this pressure by reshaping the world’s $5 trillion agriculture business – for the better.

Firstly, timing in farming is essential. When will the heatwave end? How long until the next big storm? When will the floods start? Finding answers to these pressing questions determines farmers’ ability to know when to buy seed, what seed to buy and when to plant and harvest it.

Farmers need these answers several months in advance, sometimes even six months ahead, to guarantee their crops. This is even more important today as the severity of unpredictable weather patterns is accelerating. However, Gupta says most weather forecasts are still only two weeks ahead.

Farmers also need agritech to help them understand how viable their soil – the core of their livelihood – will be in decades’ time as climate patterns evolve faster than anticipated.

Overall, farmers need far more notice, both for the ‘here and now’ and the ‘what’s next?’. AI-based technologies have the potential to provide that clarity, giving more accurate, detailed and frequent forecasts.

Understanding the difference between weather and climate is vital for farmers as they adjust their operations to keep pace with a changing world.

Understanding the difference between weather and climate is vital for farmers as they adjust their operations to keep pace with a changing world.

Secondly, AI and other agritech can increase the supply of urgently needed climate-resistant seeds, accelerating the time it takes to get from the laboratory to the soil. It currently takes 10 to 15 years to launch a new seed, but Gupta says weather patterns can shift significantly in that time. Seeds can become less resilient and crops can fail.

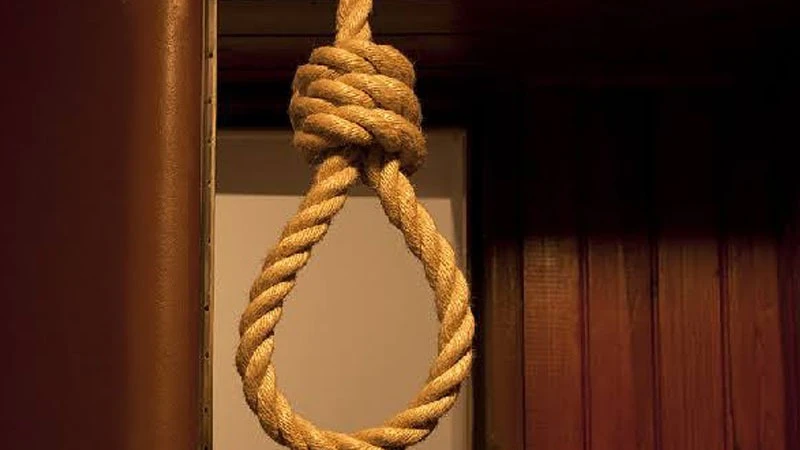

This puts considerable stress on the farming community, sometimes making it difficult to attract new talent. While working with the Government of India, Gupta “saw examples where a lot of cotton farmers either committed suicide, left cotton farming altogether or moved to work as labourers in big cities”. This is not an isolated problem, with 95% of young farmers saying poor mental health is the biggest hidden danger in farming today.

Building data banks for farmers

The effectiveness of AI – both in weather forecasting and shaping climate-resistant seeds – heavily relies on the data ‘fed’ into the system. The quality, volume and application of data from farms and other parts of the agricultural supply chain must improve worldwide, though there are already clear differences between developed and developing nations.

In developed nations, a lot of available data can be better gathered, shared and used to increase the accuracy of weather forecasts. Instead of farmers in Spain being told to prepare for a heatwave, for example, AI can determine that tomato farmers in a localized part of Spain should buy a particular type of seed later than plan to protect that specific crop. Gupta says this sort of detail “drives action”, safeguarding harvests, farmers and seed companies.

There is little data in developing countries, however, which can put the communities most vulnerable to food instability at an even greater risk. The head of a village in India would often record the estimated rainfall in that area in a notebook, for example, which Gupta warns can bring unintended bias. In turn, this feeds weaker data into AI systems for that area. His team is now investigating ways to create higher-resolution weather forecasts with little data.

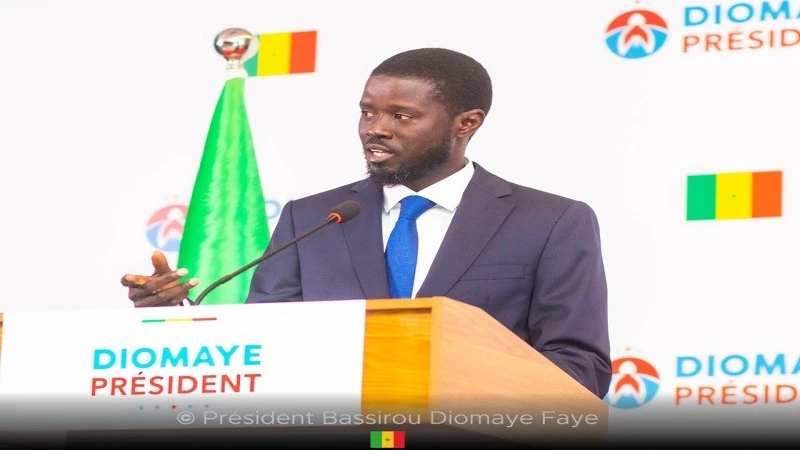

AI enables a range of advanced systems to elevate the efficiency, quality and economic potential of farming worldwide. Image: World Economic Forum

Agritech: The bigger picture

The report is the second paper from the Forum’s AI for Agriculture Innovation (AI4AI) initiative, which aims to scale agritech services through public-private partnerships. It elaborates on the role of agritech in shaping the agriculture ecosystem across four broad categories: intelligent crop planning, smart farming, farmgate-to-fork, and data as an enabler.

The power of applying agritech services in agriculture was illustrated by the Saagu Baagu pilot project, which the Forum conducted with the government of Telangana in southern India. Four agritech services were introduced to 7,000 chilli farmers, whose absolute profits climbed by 18%. The project is now being scaled up to support 500,000 farmers planting 5 crops in 10 districts. Here’s a deeper look at each of the four categories:

Intelligent crop planning

In this context, AI helps create a ‘crop plan’ that considers forecasts for the changing climate and customers’ nutritional needs. It can also correct minor errors in real time, stopping them from magnifying into a bigger challenge months later during the harvest.

Soil testing at the early stages of crop planning is also imperative, the report notes, and AI-based models mean tests that used to take a few weeks now happen in real time. Farmers can then act immediately if they choose to. They can also benefit from the gene editing of seeds using predictive AI tools, which achieves higher yields while using similar resources – the ultimate goal in the future of agriculture.

Smart farming

Farmers must juggle multiple unknowns every week, from weather to wildlife to price volatility. Smart farming uses technologies to help remove some uncertainty from farmers’ weekly load by focusing on precision. The report explains how soil stress, efficiency of operations and detecting and avoiding risks early on are part of this new approach to farm management.

AI and augmented reality (AR) for crop management, advice on crops, pests, plant diseases and nutrients are also some of the key methods in smart farming that are already making an impact on the ground, the report details. Agerpoint, which creates 3D models of crops and trees, uses thousands of laser beams pointed at a plant simultaneously to create a digital twin of the plant, so farmers extract knowledge from the sensors rather than the live plant.

Robotics is another game changer for smart farming. Being able to programme a robot to sow and remove weeds automatically across many acres of fields – some tools can kill 300,000 weeds per hour – saves farmers considerable time, stress and physical strain, for example.

Leveraging technologies – on the ground and in space – to give farmers and seed companies greater visibility vastly improves efficiency and quality.

Leveraging technologies – on the ground and in space – to give farmers and seed companies greater visibility vastly improves efficiency and quality. Image: World Economic Forum

Farmgate-to-fork

Being able to track every second of inventories’ movements in warehouses enabled by the Internet of Things (IoT) is an effective way of reducing this risk. Such transparency is especially relevant in our hyperconnected world where a quarter of all food produced for human consumption is internationally traded. IoT also means maintenance can be undertaken before any error occurs, keeping national and global supply chains on track.

The value of smart packaging prevents food-borne diseases and tracks food’s quality and its environment through chemical or biosensors, the report notes. These include temperature, pathogens, freshness, and leaks of hundreds of millions of products brought to market by farmers every day worldwide. Such safeguards mean farmers can capture quick returns and competitive prices while customers get the high-quality food they need.

Data as an enabler

Data is a key ingredient to making AI effective. Knowing how the soil quality, temperature and rainfall have affected a farm over the years immediately gives AI-based tools a springboard to create accurate forecasts and climate-resistant seeds for farmers, for example.

Farmers can also use data to craft their own unique identity, the report says. Improving digital public infrastructure (DPI) can be especially crucial for enabling agritech services in emerging economies. It provides an understanding of “who I am” (identity), “where I am” (georeferenced farm location) and “what I am growing” (crops sown and the area under cultivation). Combined, these three points mean a farmer can position themself as a distinct enterprise – building their reputation, elevating farm operations and strengthening profitability.

Using data to create climate-smart agriculture – such as information on the effect of weather patterns in particular locations – also helps farmers adapt to longer-term scenarios while supporting crops today. A similar level of reassurance is seen in reducing farmers’ vulnerability to supply or price shocks. The report outlines three key datasets that can help: data on the area under cultivation, sowing time and the possible harvest time, and the quantity of the harvest.

Learning how to harness the value of data from farming methods can help strengthen farmers’ crops in coming years.

Building AI-inclusive farms

The rollout of new technologies since the 1970s has created more inequality, Gupta says, notably the digital divide where at least a third of the world’s population is still not online. AI is “not something that just us AI entrepreneurs should be talking about. It is something that the entire society, even the big corporates, should be talking about,” says Gupta.

Currently, only a quarter of farmers in the US, one of the world’s leading agricultural exporters, use an internet-connected device to access data relating to farming, the report points out. Plus, 30% of farmers cited unclear return on investment (RoI) as one of the top three reasons for not adopting agritech.

This suggests the level of education on the value of agritech must improve, especially in emerging economies. The 62% of European farmers adopting technology is in stark contrast to the 9% of farmers in Asia, especially when Asia’s population is three times larger than any other continent worldwide, with 4.7 billion people.

Gender discrimination is also very prominent, finds the report. Women account for 43% of the agriculture workforce globally, yet they have little influence in decision-making. Women’s limited access to smartphones is part of the problem, as the majority of agritech services are delivered via mobile phones. Currently, women are 7% less likely than men to own a mobile phone, which translates into 130 million fewer women having a phone than men – equivalent to twice the size of the UK’s entire population.

By Pooja Chhabria and Michelle Meineke

Top Headlines

© 2024 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED